Patriots of Color

Patriots of Color

Patriots of Color

Patriots of Color

Brief summaries of "Patriots of Color," (with permission) from Copyrighted "Volumes 1 & 2" of the extensive "Patriot Chronicles" series compiled and written by: George Quintal Jr. The service of "Patriots of Color" rendered to the United States of America must not be forgotten, but remain as an essential part of America's heritage and history.

Contents:

Patriots of Color© - By George Quintal Jr.

James Armistead - Virginia slave, working with General Marquis de Lafayette as a spy - By Wallbuilders

(See also: Services of Colored Americans, in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 & The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution By William C. Nell, And The Negro in the American Revolution by Benjamin Quarles)

![]() Home

Home

![]() About

About

![]() Contact

Contact

![]() Search

Search

![]() News,

Commentary, & Action

News,

Commentary, & Action ![]() Recommended Books

Recommended Books

|

Patriots of Color at Battle Road

|

Copyright © George Quintal Jr.

All Rights Reserved

Only Version Authorized by the Author. Please do not purchase/access/cite outdated or pirated versions. |

Patriots of Color at Bunker Hill And the Siege of Boston 17 June 1775

|

Short biographies of "Patriots of Color"

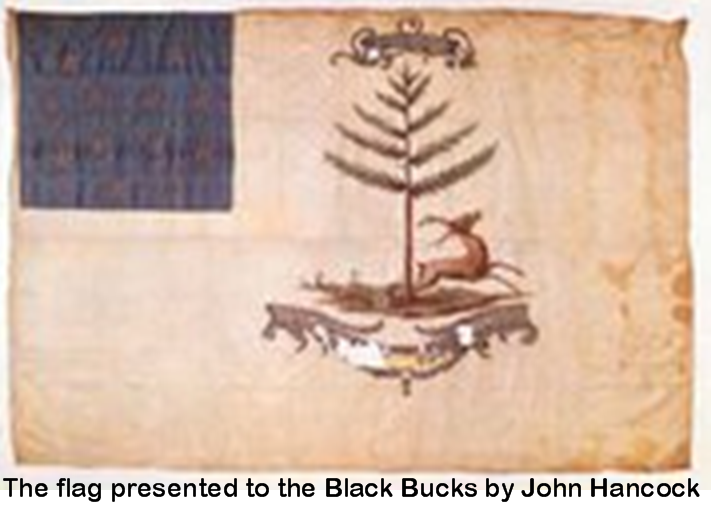

In addition to the integrated units, there were also three all Black units that served: the Rhode Island First regiment, who fought with distinction at Newport, Monmouth and Yorktown; the Black Bucks of America, a Massachusetts regiment whose banner is still on display at the Massachusetts Historical Society; and the Volunteer Chasseurs, a regiment from Haiti brought over by our French allies. The latter unit took the ideas of liberty back to Haiti with them. Those ideas were used to overthrow their French masters and create the second republic in the Americas.

Regarding "Patriots of Color at

Bunker Hill," the late Dr. Alfred F. Young, Senior Research Fellow, Newberry

Library, Chicago (2002) in the Preface states:

“Every once in a while a

piece of scholarship comes along that changes the way you look at a historical

event. The prevailing wisdom about the Battle of Bunker Hill is that only a

handful of African American soldiers were there. After almost three years of

research George Quintal reports that there very likely were 103 “patriots of

color” at Bunker Hill (and may have been as many as 150).

…Quintal is not an historian of black history. A

native of Maine, he began his foray into common soldiers almost three decades

ago in pursuit of twelve of his own ancestors who were in the Revolutionary War.

He is a self-taught genealogist and military researcher, skilled as a computer

specialist. Beginning with an interest in the expedition to Canada led by

Benedict Arnold, he moved into the Battles of Bunker Hill and Saratoga. Then he

began to read systematically the 2670 microfilm reels of pension applications

filed by veterans in 1820 and 1832, a huge treasure trove of evidence about the

ordinary soldiers, largely unmined by historians. The scope of his research on

the patriots of color at Bunker Hill and Battle Road is staggering.”

From the Introduction of Patriots of Color at Bunker

Hill Mr. Quintal explains: “While the stories of handfuls of soldiers

of color (such as PETER SALEM) have often been told, this project has restored

those stories, added to them significantly and presented the new stories of many

other men of color who served at Bunker Hill. Much has been learned during this

effort about the individual lives of those men such as their status

(slave/free), their age, where they served, how they lived, who they married,

where they resided and where they died. One of the ways that I try to honor

these men is to attempt to trace their family genealogies down to their

grandchildren, to possibly link the distant past with a descendant in the

present.

…A large number of the men who responded to the

Lexington Alarm, including the men of color, set up camp at Cambridge Common and

Harvard College. They were encouraged to stay on duty and most became

eight-month’s men, due to their agreed term of service. A land encirclement of

British-held Boston was instituted, an action called the Siege of Boston. Next

came the Battle of Bunker Hill on 17 June 1775. Less than a month later, on 3

July, George Washington took command in Cambridge and set to work to ultimately

transform these rag-tag farmer/soldiers into disciplined fighters in the

Continental Army, Significant numbers of the soldiers of color in this great

mass of Patriots had the newly-minted status of ‘free man.’ An irrepressible

spirit of liberty was in the air. What a time to have been alive!”

Below, discover summaries of but a few "Patriots of

Color."

Caesar Augustus -

Augustus was the last colonist wounded in the

Battle of Lexington. He was from Dorchester,

Massachusetts.

Prince Easterbrooks

-

Prince Easterbrooks was also known as

Estabrook. In the very first battle of the

American Revolution, the Battle of Lexington,

there were no fewer than ten black patriots.

Easterbrooks was one of them. He served under

Captain John Parker, the first to engage in the

war. He was wounded when the British forces

fired upon the citizens of the town. He was

mentioned in the Salem Gazette or Newberry and

Marblehead Advertiser for April 21, 1775, as

a "Negro man" who was "wounded (Lexington) ." Salem did not serve alone in this battle.

Salem Poor, Prince Hall, and Philip Abbott also

distinguished themselves in this battle. Salem

is considered one of the heroes of Bunker Hill.

He had 14 accommodations that day for his acts

of bravery and was acknowledge as a great leader

of men. He received his honors before Washington

himself. "A negro man belonging to Groton, took aim at

Major Pitcairn, as he was rallying the dispersed

British Troops, and shot him through the head,

he was brought over to Boston and died as he was

landing on the ferry ways. It has long been

known that Pitcairn was killed by a negro, but

this is the first time perhaps that he has ever

been connected to Groton." ~ Groton Historical Series by Dr. Samuel A.

Green, Vol IV, 1899, p. 259 Salem joined the Fifth Massachusetts Regiment

and served in the battles of Concord and

Saratoga. He served for seven years, a length of

time few other soldiers could match. Though a

slave at the beginning of his service, he was

a free man by the end. At the end of the war, in

1783, he married. In honor of his service, Salem was given a

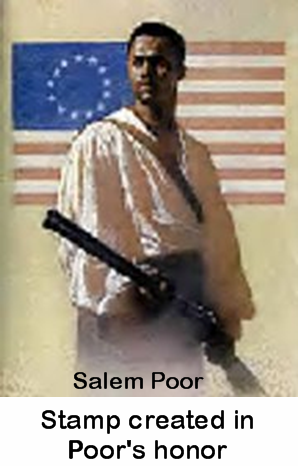

wool bounty coat. Poor fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill in

Colonel Frye's Regiment and is credited with

shooting British Lt. Col. James Abercrombie. He

conducted himself so well during the battle,

that no less that 14 officers, including Colonel

William Prescott himself, petitioned the

legislature of Massachusetts declaring that Poor

had behaved like an experienced officer and

brave soldier and "a reward was due to so great

and distinguished a character." Of all the men

who served in the battle, Poor was the only one

singled out for such an honor. What he did

specifically to earn such praise is unknown, as

the petition states, "to set forth the

particulars of his conduct would be tedious."

Some historians think this indicates that Poor's

acts of bravery were too numerous to lay out. Poor also fought in the Battle of Saratoga,

which was the turning point of the war, and at

the Battle of Monmouth. He was honored with a U.S. postage stamp.

Phillip Abbot - Abbot was a servant to the family of

Nathaniel Abbot of Andover, Massachusetts. When

Nathaniel Abbot's men were called to the Battle

of Bunker Hill, Phillip Abbot fought and died

along side them. Jack Arabus - Jack Arabus was a slave of a wealthy

Connecticut merchant. As was common in those

days, a person could pay someone to take their

place in the military. Arabus' owner offered him

his freedom if he would fight in the place of

the merchant's son. Arabus accepted the offer

and found in the American Revolution. Sadly,

upon his return from war, his master changed his

mind. Arabus decided to take matters into his own

hand and ran away. He was not free for long. He

was captured the next day and put in jail in New

Haven. His master sued for his return, but

Arabus had a defender. The Yale educated lawyer,

Chauncey Goodrich, took on his case. He won. The

judge ruled that Arabus was free the moment he

went to fight. The agreement did not matter.

This case enabled hundred of enslaved black

patriots to win their own freedom as they had

won their country's Charles Bowles - Bowles was born in Boston in 1761. He was

mixed race, his father was an African and his

mother was the daughter of Colonel Morgan. At

the age of 14, Bowles enlisted in the

Continental Army. Her served during the entire

length of the war. His first two years he spent

in the service of an officer, but then

reenlisted to fight. After the war, he moved to

New Hampshire and became a farmer. There is a

story that he had been a slave to a Tory family,

but that would not be correct if his mother was

white. He might have been a servant.

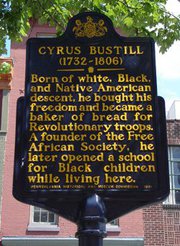

After the war, Bustill and his wife, who also

mixed race - the daughter of an Englishman and a

Delaware Indian, moved to Philadelphia. There

they and their eight children attended Quaker

meetings. Bustill was also an early member of

the Free African Society which began in 1787.

This is the society established by black

Founders Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. When

Bustill retired as a baker, he opened a school.

He dies in 1806. Oliver Cromwell - Oliver Cromwell was born in the colony of New

Jersey, near Burlington. There seems to be some

confusion on his birth date. One source has it

as May 24, 1753, while another puts it in 1752.

He was light skinned, a farmer, and was raised

by the family of John Hutchin. It is possible

that he was born a free black. He served in the second New Jersey regiment

under Captain Lowery and and Colonel Israel

Shreve. He served in the battles of Trenton,

Princeton, Brandywine, Monmouth, and Yorktown.

He made the famous crossing of the Delaware on

December 25, 1776. George Washington personally signed

Cromwell's discharge papers at the end of the

war. Washington also designed a medal which was

presented to Cromwell. He later applied for a

pension as a veteran. He could not read or

write, but he was very well liked in the

community of Burlington. Local lawyers, judges,

and politicians helped him to get the pension of

$96 a year. Cromwell purchased a 100 acre farm,

fathered 14 children, and moved into Burlington

in his later years. He outlived 8 of his

children, and died when he was 100 years old. He

is buried in the Methodist churchyard in

Burlington, where some of his descendants still

live. Fraunces is also known to have helped feed

the 13,000 American prisoners of war kept around

New York City, including those kept on the

notorious prison ships. Fraunces and his wife, Elizabeth Dailey, had

seven children, one by the name of Elizabeth,

but called Phoebe. During the Revolution,

Washington came to stay at a place called

Mortier House in New York Cith. He wrote to ask

Fraunces to find for him a housekeeper. Fraunces

sent his daughter Phoebe. It is possible that he

sent her because he had heard a rumor that an

attempt was to be made on Washington's life, or

it may be that Phoebe discovered this plot while

working at Mortier House. Either way, one of

Washington's body guards, Thomas Hickey, was

executed for attempting to poison the general.

Phoebe and her father are credited with

discovering the plot, and Fraunces is credited

with removing the poisoned peas intended for

Washington's dinner. Phoebe was ten years old at

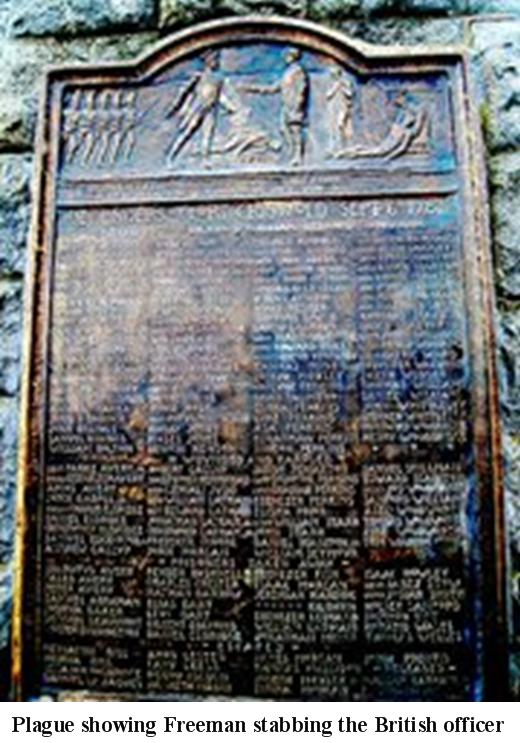

the time of Hickey's execution in June of 1776. Finally, the British were able to capture the

fort. A British captain asked who was in charge

of the fort. Colonel William Ledyard answered,

"I did once. You do now." As he stepped forward

he offered his sword to the British officer, a

sign of surrender. The officer took

Ledyard's sword and thrust it into his body to

the hilt. “Lambert . . . retaliated upon the

[British] officer by thrusting his bayonet

through his body. Lambert, in return, received

from the enemy thirty-three bayonet wounds, and

thus fell, nobly avenging the death of his

commander.” The British response to the death of their

captain and other officers was to slaughter

every man, including Freeman. A plaque at the

fort honors these men for their bravery. Freeman had been the slave of Ledyard, but

had been freed. Freeman stayed living near his

former master, married, and enlisted when the

fighting began, serving side-by-side with his

former master. A month after the Boston Massacre, Hall was

freed by his master, his certificate of

manumission stating he was "no longer Reckoned a

slave, but [had] always accounted as a free

man." Hall then worked as a peddler, caterer and

leather dresser. He was even listed as a voter

and a taxpayer. He owned a small house and

leather workshop in Boston. Did he fight? There were six men in

Massachusetts named Prince Hall, but it is

believed that he was the Prince Hall that served

in the Battle of Bunker Hill. He also supplied

leather drum heads to the Continental Army, as a

bill he sent to Colonel Crafts in April of 1777

shows. Before the war began, Hall and 14 other free

black men had joined the British Army Lodge of

Masons. When the British retreated from Boston,

these men formed their own lodge, the African

Lodge #1, which was later renamed in Hall's

honor. it took 12 years to get the official

charter. Hall was the first Grand Master. This

lodge was the first ever black lodge. Hall became one of Boston's most prominent

citizens and a leader in the black community. He

spoke out against slavery and the denial of the

rights of blacks. After years of complaining of

the lack of schools for black children, he set

one up in his own home. In his last published

speech, at the lodge in 1797, he spoke out

against violence. "Patience, I say; for were we not possessed

of a great measure of it, we could not bear up

under the daily insults we meet with in the

streets of Boston, much more on public days of

recreation. How, at such times, are we

shamefully abused, and that to such a degree,

that we may truly be said to carry our lives in

our hands, and the arrows of death are flying

about our heads....tis not for want of courage

in you, for they know that they dare not face

you man for man, but in a mob, which we

despise..." He died in 1807. It was a year after his

death that the lodge he founded decided to honor

him by renaming itself The Prince Hall Grand

Lodge. When his indenture ended in 1774, Haynes

enlisted as a "Minuteman" in his local militia.

Though he did not fight in the Battle of

Lexington, he did write a ballad-sermon about

it. The poem dicussed the conflict between

slavery and freedom but did not address black

slavery. He took part in the Siege of Boston and

the expedition to Fort Ticonderoga led by Ethan

Allen and the Green Mountain Boys. After the war, Haynes had an opportunity to

study at Dartmouth College. He turned it down.

Instead he took up the study of Latin and Greek

with a Connecticut clergyman. By 1780, he was

able to receive his license to preach. His first

congregation was a white one in Middle

Granville. He eventually presided over white and

mixed congregations in four different states,

including New York and Massachusetts. Later he

married a white school teacher by the name of

Elizabeth Babbitt. He was ordained in the

Congregationalist Church in 1785, the first

black to be so by a mainstream protestant

church. For more than 30 years, Haynes presided over

a mostly white church in Rutland, Vermont.

During his time there, he developed an

international reputation as a preacher and a

writer. In 1801, he published a track called

"The Nature and Importance of True

Republicanism." This contained his only

published statement on race and slavery. He did

argue for the abolition of slavery by arguing

that it denied black men their rights to "life,

liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." He also

said, "Liberty is equally as precious to a black

man, as it is to a white one, and bondage as

equally as intolerable to the one as it is to

the other". In 1804, he became the first black

man in America to receive a masters degree,

earning it from Middlebury College. He was also

a friend and counselor to the presidents of

Harvard and Yale universities. Haynes left Rutland in 1818 due to conflicts

over politics, Haynes was a fervent Federalist,

and style. Sadly, after living and working with

the people of Rutland for 30 years, there was

speculation that the departure was due to his

race. Haynes final appointment to a church was in

Manchester, Vermont. There he counseled two men

who were condemned to death for murder. Their

convictions were overturned when their victim

reappeared quite alive. Haynes wrote a best

seller about the seven year ordeal. The book

stayed a best seller for a decade. During the last decade of his life, Haynes

ministered to a church in New York. He died in

1833, at the age of 80. His tombstone read, “Here lies the dust of a poor hell deserving

sinner, who ventured into eternity trusting

wholly on the merits of Christ for salvation. In

the full belief of the great doctrines he

preached while on earth, he invites his

children, and all who read this, to trust their

eternal interest on the same foundation.” Haynes was a great admirer of George

Washington. He was a member of the Washington

Benevolent Society, and every year he would

preach a special sermon on Washington's

birthday. Benjamin Scott Mayes

- Benjamin Mayes, nicknamed Daddy Ben, was a

royal prince in Africa. He was brought to

America and sold to a Colonel Scott. During the

Revolution, the British wanted to find Colonel

Scott. They could not find him, but they did

capture Mayes. In an attempt to get him to

reveal the whereabouts of Scott, the British

hung Mayes and cut him down before he was dead.

They did this not once, not twice, but three

times. Despite this torture, Mayes refused to

divulge his master's hiding place. For his

bravery and loyalty, Mayes was awarded a gold

medal and the admiration of the people of what

is now Maury County, Tennessee. He died in 1829. Jordan B. Noble - Jordan Noble was born in Georgia around 1800,

so he did not serve in the American Revolution,

at least not the first one. He moved to

Louisiana, whether on his own or not is unknown.

At the age of just 13 he served as a drummer boy

during the War of 1812, sometimes called our

second revolution. He served under General

Andrew Jackson with the Seventh Louisiana

Regiment. During this time, musicians were a

vital part of the military. They would

communicate commands with their instruments.

Noble beat his drums in many famous battles and

events. Noble also served in the Seminole War in

Florida in 1836. He also was one of the few

blacks to serve in the Mexican American War. John Redman - John Redman served in the First Virginia

Regiment of Light Dragoons. A dragoon is a

mounted soldier who fights with sabers, pistols,

and carbines. Not much else is known about

Redman, except that on June 11, 1823, he applied

for a veteran's pension as a veteran of the

American Revolution. He was awarded his pension

one week later. He was one of the few black men

to be a member of a cavalry unit. Again in 1781, the Rhode Island First came to

the rescue. At the Battle of Croton River, their

commander, Colonel Greene was mortally injured.

William Nell, who published a book in 1855 about

the black Patriots, wrote, “Colonel Greene, the commander of the

regiment, was cut down and mortally wounded: but

the sabres of the enemy only reached him through

the bodies of his faithful guard of blacks, who

hovered over him, and every one of whom was

killed.” Even though there the wound was fatal, some

of the men of the Rhode Island First formed a

barrier around him, choosing to die with their

commander rather than abandon him to the enemy.

The rest of the unit continued the fight and the

war. A remnant of the original regiment was

present with Washington at the Surrender at

Yorktown. Prince Sisson and the Commandos

- In December of 1776, Washington's second in

command, General Charles Lee was captured by the

British. The only hope of getting him back was a

prisoner exchange. But the Americans did not

have a British prioner that was equal to Lee.

Lt. Colonel William Barton formed a plan. He

would take some men, slip past the British

pickets at Newport, Rhode Island and capture

General Richard Prescott. Barton selected 40 of his best men, black and

white, for the mission. He warned them of the

danger and asked for volunteers. Every man

stepped forward. The group waited until the middle of the

night before climbing into rowboats. They

wrapped fabric around the oars to muffle the

sound and rowed right past the British gunboats

anchored in the harbor. When they reached the

shore near the generals' head quarters, they

quickly over powered his guards and entered his

house. His door was locked. At that moment, one of Barton's men, Prince

Sisson, threw himself at the door, hitting it

with his head. Sisson was a large and powerful

man. The door gave and Sisson entered the

room and grabbed the general. Barton's men

quickly made their escape with their

prisoner. Prescott was subsequently exchanged

for General Lee. William Nell, in the 1852 book

The

Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

said, "As was customary, Prince took the surname of

his owner, William Whipple, who would later

represent New Hampshire by signing the

Declaration of Independence. . . . When William

Whipple joined the revolution as a captain,

Prince accompanied him and was in attendance to

General Washington on Christmas night 1776 for

the legendary and arduous crossing of the

Delaware. The surprise attack following the

crossing was a badly needed victory for America

and for Washington’s sagging military

reputation. In 1777, [William Whipple was]

promoted to Brigadier General and [was] ordered

to drive British General Burgoyne out of

Vermont." An 1824 work provides details of what

occurred after General Whipple’s promotion: "On [his] way to the army, he told his

servant [Prince] that if they should be called

into action, he expected that he would behave

like a man of courage and fight bravely for his

country. Prince replied, “Sir, I have no

inducement to fight, but if I had my liberty, I

would endeavor to defend it to the last drop of

my blood.” The general manumitted [freed] him on

the spot." True to his word, Whipple enlisted as a

soldier in the Continental Army. Besides serving

during the famous crossing of the Delaware on

Christmas in 1776, where he has been depicted as

an oarsman for Washington's boat, he also fought

in the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 and the Battle

of Rhode Island in 1778. He also served as a

high ranking aide on Washington's general staff.

Peter Williams - Peter Williams was a clergyman living in New

York City. When the British invaded New York,

Williams moved to the town of New Brunswick in

New Jersey. After the war, his son wrote of

Williams actions against the British, "In the Revolutionary War, my father was

decidedly an advocate of American Independence,

and his life was repeatedly jeopardized in its

cause...He was living in the State of [New]

Jersey, and Parson Chapman, a champion of

American liberty of great influence throughout

that part of the country, was sought after by

the British troops. My father immediately

mounted a horse and rode round his parishioners

to notify them of his danger, and to call on

them to help in removing him and his goods to a

place of safety." ~ The Colored Patriots of the American

Revolution by Wm Cooper Neil & Harriet Beecher

Stowe 1855 In fact, a number of state constitutions

protected voting rights for blacks. The state

constitutions of Delaware, Maryland,

Pennsylvania (all 1776), New York (1777),

Massachusetts (1780), and New Hampshire (1784)

included black suffrage. In 1874, Robert Brown

Elliot, a member of the House of Representatives

from South Carolina and a black man,

stated "When did Massachusetts sully her proud

record by placing on her statute-book any law

which admitted to the ballot the white man and

shut out the black man? She has never done it;

she will not do it." However, no state allowed slaves to vote and

in South Carolina no free blacks could vote.

When it was brought to the state for

ratification, our Constitution was voted on

by white and black citizens. In Baltimore,

Maryland, more blacks voted than whites. Besides

the right to vote, blacks in many of the states

could hold office as did Wentworth Cheswell. The

blacks used their votes well, working along side

white abolitionists to end slavery in several

states. These included Pennsylvania,

Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island,

Vermont, New Hampshire, and New York. It has also been suggested that the

Constitution was a proslavery document. Is

it? There are only three references to the

institution of slavery in the Constitution. The

first is in Enumeration Clause in Article 1,

Section 3. This is the famous 3/5 clause which

some have pointed to as proof that the Founders

viewed blacks as less than white. That may be

true of some individuals, but not of the clause

or the ideas behind the Constitution. Some

delegates to the Constitution, especially

those that were against slavery, argued that

since slaves were considered property, they

should not counted at all. The southern states

wished them to be counted as a full person since

their large slave populations would give those

states greater representation and more power in

Congress. A compromise was reached, the 3/5

clause. The effect of that clause was to reduce

the number of representatives in the House for

states with large slave populations and thereby

reduce their power. This makes the clause

antislavery. The second mention is in Article 1, Section

9. In this section a date was set to end the

importation of slaves. This was another

compromise. It allowed the slave trade to

continue for a period of twenty years, but then

end it. It would be difficult to consider the

ending of the slave trade as a proslavery

clause. The final mention of slavery is in Article 4,

Section 2. This is the Fugitive Slave clause.

That section of the Constitution deals with the

states, their citizens, and extradition from one

state to another. It holds that people who are

bound in service in one state, cannot be excused

from it because of the laws of another state.

This is the most proslavery section of the

Constitution since it allows owners to retrieve

runaway slaves from other states, even those

that outlawed slavery, but it alone does not

make the Constitution proslavery. Federal efforts against slavery did not end

with the Constitution. In 1789, Congress passed

a law which banned slavery in all federal

territories. Five years later, in 1784, another

antislavery law was passed. This one forbade

exporting slaves from any state. Sadly, this progress did not continue. As

many of the generation of the Revolution passed

away, so did many of their ideals. Beginning in

the early 1800s, new laws were passed that

limited the rights of blacks and

women. This was in part, a political move by one

party to limit the influence of the other, but

it also reflected a loss of the

revolutionary ideals. In 1809, Maryland

disenfranchised black voters. Other states

followed suit, such as North Carolina in 1835.

Even before they were formally denied the vote,

many blacks and women were prevented from voting

by their white neighbors. This foreshadowed the

treatment blacks would receive following the end

of Reconstruction. In 1820, with the passage of the Missouri

Compromise, the few remaining Founders began to

fear that slavery would destroy the

country. Elias Boudinot said it woud be "an end

to the happiness of the United States." John

Adams went further by saying that removing the

prohibition against slavery in the territories

would bring an end to the United States. Thomas

Jefferson lamented, I had for a long time ceased to read

newspapers, or pay any attention to public

affairs, confident they were in good hands, and

content to be a passenger in our bark to the

shore from which I am not distant. But this

momentous question, like a firebell in the

night, awakened and filled me with terror. I

considered it at once as the knell of the

Union." At this time, Congress also enacted the

Fugitive Slave Law which allowed slave owners to

enter free states to find their runaways. It

also enabled the kidnapping and enslavement of

many free blacks by claiming they were runaways.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act pushed the country

farther along the road that would take us to

war, where finally, the slavery question would

be settled.

Peter

Salem -

Salem was a slave and

a celebrated marksman. After the Battles of

Lexington and Concord soldiers from all over

Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island

assembled outside of Boston to confront the

5,000 British troops stationed there. That

confrontation, the Battle of Bunker Hill, began

well for the Americans until they began to run

out of ammunition. At that point, Major John

Pitcairn, who had lead troops at the Battle of

Lexington, mounted the hill and called "The day

is ours!" The day may have been a victory for

the British, but it came at a dear price. Salem

raised his musket and shot Pitcairn, throwing

the British into confusion.

Peter

Salem -

Salem was a slave and

a celebrated marksman. After the Battles of

Lexington and Concord soldiers from all over

Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island

assembled outside of Boston to confront the

5,000 British troops stationed there. That

confrontation, the Battle of Bunker Hill, began

well for the Americans until they began to run

out of ammunition. At that point, Major John

Pitcairn, who had lead troops at the Battle of

Lexington, mounted the hill and called "The day

is ours!" The day may have been a victory for

the British, but it came at a dear price. Salem

raised his musket and shot Pitcairn, throwing

the British into confusion. Salem Poor

-

Salem Poor was born in the 1740s. He had

purchased his freedom in 1769 for 27 pounds,

which was a year's salary for a working man. He

married a free black woman by the name of Nancy.

Before the war began, they had a son. When the

war began, he left behind his family to serve

the Patriot cause.

Salem Poor

-

Salem Poor was born in the 1740s. He had

purchased his freedom in 1769 for 27 pounds,

which was a year's salary for a working man. He

married a free black woman by the name of Nancy.

Before the war began, they had a son. When the

war began, he left behind his family to serve

the Patriot cause. Seymour Burr -

Seymour Burr, also spelled Seymore, was the

slave of the brother of Colonel Aaron Burr, also

named Seymour. Burr was from the colony of

Connecticut. During the American Revolution,

Burr ran away to join the British Army who was

promising freedom to slaves who enlisted. Burr

was found by his master before he could enlist.

His master offered him his freedom if he would

enlist in the Continental Army instead. Burr

enlisted in the Massachusetts Seventh Regiment,

led by Colonel John Brooks. He served at the

siege of Fort Catskill, suffering cold and

starvation.

Seymour Burr -

Seymour Burr, also spelled Seymore, was the

slave of the brother of Colonel Aaron Burr, also

named Seymour. Burr was from the colony of

Connecticut. During the American Revolution,

Burr ran away to join the British Army who was

promising freedom to slaves who enlisted. Burr

was found by his master before he could enlist.

His master offered him his freedom if he would

enlist in the Continental Army instead. Burr

enlisted in the Massachusetts Seventh Regiment,

led by Colonel John Brooks. He served at the

siege of Fort Catskill, suffering cold and

starvation. Cyrus Bustill

-

Cyrus Bustill was born in Burlington in 1732.

His father was an English lawyer and his mother

a slave. Because the status of the child follows

the status of the mother, this meant that

Bustill was a slave. He was trained to be a

baker by a Thomas Prior, who was a Quaker. At

the age of 36, Bustill got his freedom. During

the American Revolutiion he helped the army with

something it had a great need for, bread. He was

commended for this service and received a silver

piece for General George Washington.

Cyrus Bustill

-

Cyrus Bustill was born in Burlington in 1732.

His father was an English lawyer and his mother

a slave. Because the status of the child follows

the status of the mother, this meant that

Bustill was a slave. He was trained to be a

baker by a Thomas Prior, who was a Quaker. At

the age of 36, Bustill got his freedom. During

the American Revolutiion he helped the army with

something it had a great need for, bread. He was

commended for this service and received a silver

piece for General George Washington. Samuel and Elizabeth "Phoebe" France

- Samuel Fraunces was a mulatto, a person with

one whie and one black parent, from Jamaica. His

was most likely born in 1734, though it could

have been as early at 1722. At some point in his

life he immigrated to the colonies and settled

in New York City, eventually becoming the owner

of a tavern. It was rumored that during the

Revolutionary War, his tavern was used as a

meeting place for Patriots. On December 4, 1783,

George Washington delivered his farewell to his

officers at Fraunce's Tavern. Apparently

Washington and Fraunces had a personal and

business relationship. The two dined together at

the Old 76 House in Tappan, New York, and

Fraunces cooked for Washington at the DeWint

House, which is also in Tappan. Fraunces also

served a steward to President Washington in New

York City, and in Philadelphia from 1791 to

1794. George Washington Parke Custis, Martha's

grandson, remarked on Fraunces at a state

dinner, "Fraunces in snow-white apron, silk

shorts and stockings, and hair in full powder,

placed the first dish on the table, the clock

being on the stroke of four, 'the labors of

Hercules' ceased."

Samuel and Elizabeth "Phoebe" France

- Samuel Fraunces was a mulatto, a person with

one whie and one black parent, from Jamaica. His

was most likely born in 1734, though it could

have been as early at 1722. At some point in his

life he immigrated to the colonies and settled

in New York City, eventually becoming the owner

of a tavern. It was rumored that during the

Revolutionary War, his tavern was used as a

meeting place for Patriots. On December 4, 1783,

George Washington delivered his farewell to his

officers at Fraunce's Tavern. Apparently

Washington and Fraunces had a personal and

business relationship. The two dined together at

the Old 76 House in Tappan, New York, and

Fraunces cooked for Washington at the DeWint

House, which is also in Tappan. Fraunces also

served a steward to President Washington in New

York City, and in Philadelphia from 1791 to

1794. George Washington Parke Custis, Martha's

grandson, remarked on Fraunces at a state

dinner, "Fraunces in snow-white apron, silk

shorts and stockings, and hair in full powder,

placed the first dish on the table, the clock

being on the stroke of four, 'the labors of

Hercules' ceased." Jordan Freeman and Lambert Latham -

In 1781, at the Battle of Groton Heights near

New London, Connecticut, 185 Patriots, black and

white, tried to hold off the 1,700 British led

by that turncoat, Benedict Arnold. So heavily

outnumbered, the Americans had no chance for

victory, but refused to just surrender. They

retreated to nearby Fort Griswold. The British

stormed the fort. The Patriots ran out of

ammunition and began fighting with bayonets, the

butts of their muskets, and pikes. During this

last stand, Jordan Freeman speared Major

Montgomery who was leading the bayonet charge on

the fort. About the same time, Lambert Latham

picked up the American flag which had been shot

off of its poll, and held it above his head.

Jordan Freeman and Lambert Latham -

In 1781, at the Battle of Groton Heights near

New London, Connecticut, 185 Patriots, black and

white, tried to hold off the 1,700 British led

by that turncoat, Benedict Arnold. So heavily

outnumbered, the Americans had no chance for

victory, but refused to just surrender. They

retreated to nearby Fort Griswold. The British

stormed the fort. The Patriots ran out of

ammunition and began fighting with bayonets, the

butts of their muskets, and pikes. During this

last stand, Jordan Freeman speared Major

Montgomery who was leading the bayonet charge on

the fort. About the same time, Lambert Latham

picked up the American flag which had been shot

off of its poll, and held it above his head. Primus Hall - Hall was the son of Prince Hall, the founder

of the Masonic lodge that bares his name. He was

born in 1756. Primus Hall served as the servant

of Colonel Pickering. Pickering and Washington

were friends and this brought Hall and

Washington together. A story goes that after one

visit, Washington decided it was too late for

him to return to his own camp. He asked Hall if

there was enough straw and blankets to make him

up a bed for the night. Hall answered that there

was. When the officers retired for the night,

Hall busied himself until they were asleep. Then

he sat himself down upon a stool and slept.

During the night, Washington awoke and realized

that Hall had given up his own bed. Washington

then assisted that Hall join him for the rest of

the night. Hall resisted, but Washington won

out. Note, it was not unusual during this period

for men to share a bed while traveling.

Primus Hall - Hall was the son of Prince Hall, the founder

of the Masonic lodge that bares his name. He was

born in 1756. Primus Hall served as the servant

of Colonel Pickering. Pickering and Washington

were friends and this brought Hall and

Washington together. A story goes that after one

visit, Washington decided it was too late for

him to return to his own camp. He asked Hall if

there was enough straw and blankets to make him

up a bed for the night. Hall answered that there

was. When the officers retired for the night,

Hall busied himself until they were asleep. Then

he sat himself down upon a stool and slept.

During the night, Washington awoke and realized

that Hall had given up his own bed. Washington

then assisted that Hall join him for the rest of

the night. Hall resisted, but Washington won

out. Note, it was not unusual during this period

for men to share a bed while traveling.

Prince Hall - Prince Hall was born in 1735 in Boston,

Massachusetts. He was the slave of William Hall.

He father his son Primus by Delia, who was the

servant of another Boston family. In 1762, when

he was 27, he joined the Congregationalist

Church. He also married a slave by the name of

Sarah Ritchie. When Sarah died eight years

later, Hall married again, this time to Flora

Gibbs of Gloucester.

Prince Hall - Prince Hall was born in 1735 in Boston,

Massachusetts. He was the slave of William Hall.

He father his son Primus by Delia, who was the

servant of another Boston family. In 1762, when

he was 27, he joined the Congregationalist

Church. He also married a slave by the name of

Sarah Ritchie. When Sarah died eight years

later, Hall married again, this time to Flora

Gibbs of Gloucester. Lemuel Haynes - Haynes was born a free black in 1753 in West

Hartford Connecticut. He was abandoned by his

parents who were "a white woman of respectable

ancestry" and a black man. At the age of five

months, he was indentured to a David Rose of

Middle Granville, Massachussets. His indenture

was until the age of 21. According to

Haynes, “He [David Rose] was a man of singular

piety. I was taught the principles of religion.

His wife . . . treated me as though I was her

own child.” Part of the agreement for his

indenture was that he would receive an

education, which he did. “I had the advantage of

attending a common school equal with the other

children. I was early taught to read.” He

developed a passion for reading, especially

theology and the Bible. While just a teenager,

he began giving sermons in the town parrish.

Lemuel Haynes - Haynes was born a free black in 1753 in West

Hartford Connecticut. He was abandoned by his

parents who were "a white woman of respectable

ancestry" and a black man. At the age of five

months, he was indentured to a David Rose of

Middle Granville, Massachussets. His indenture

was until the age of 21. According to

Haynes, “He [David Rose] was a man of singular

piety. I was taught the principles of religion.

His wife . . . treated me as though I was her

own child.” Part of the agreement for his

indenture was that he would receive an

education, which he did. “I had the advantage of

attending a common school equal with the other

children. I was early taught to read.” He

developed a passion for reading, especially

theology and the Bible. While just a teenager,

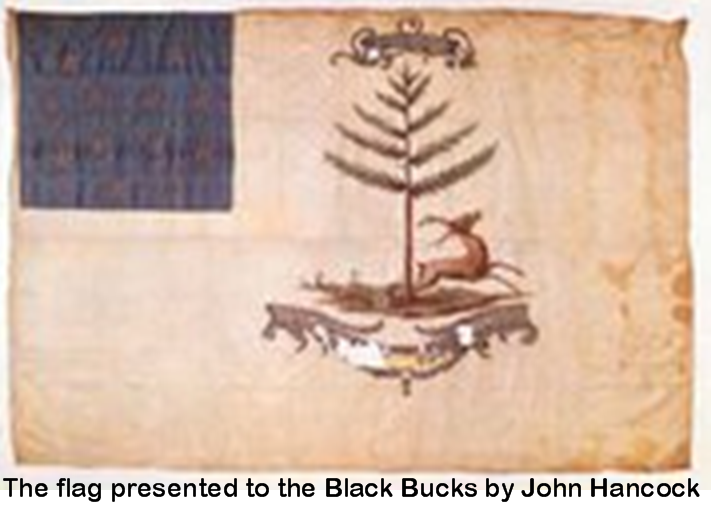

he began giving sermons in the town parrish. George Middleton and the Bucks of

America - George Middleton was a Colonel in the

Continental Army. He lead one of only three all

black units in the Continental Army. His unit,

the Bucks of America, was based out of Boston.

The dates that the Bucks were formed and

disbanded and their record of service have been

lost. However, their actions during the war

earned them recognition from one of the leading

citizens of Boston, John Hancock, who presented

the unit with a special silk flag. The flag

resides at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

He was also a member of the Prince Hall

Freemasonry Lodge, as it is believed were many

members of the Bucks. He was appointed Grand

Master in 18809. After the war he founded

African Benevolent Society in 1796. He was also

instrumental in quelling a riot in Boston. He

was also a master at breaking horses, worked as

a coachmen, and played the violin. "Freedom is

desirable, if not, would men sacrifice their

time, their property and finally their lives in

the pursuit of this?" ~ 1808

George Middleton and the Bucks of

America - George Middleton was a Colonel in the

Continental Army. He lead one of only three all

black units in the Continental Army. His unit,

the Bucks of America, was based out of Boston.

The dates that the Bucks were formed and

disbanded and their record of service have been

lost. However, their actions during the war

earned them recognition from one of the leading

citizens of Boston, John Hancock, who presented

the unit with a special silk flag. The flag

resides at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

He was also a member of the Prince Hall

Freemasonry Lodge, as it is believed were many

members of the Bucks. He was appointed Grand

Master in 18809. After the war he founded

African Benevolent Society in 1796. He was also

instrumental in quelling a riot in Boston. He

was also a master at breaking horses, worked as

a coachmen, and played the violin. "Freedom is

desirable, if not, would men sacrifice their

time, their property and finally their lives in

the pursuit of this?" ~ 1808 Rhode Island First Regiment - During the harsh winter at Valley Forge, a

new regiment was created, the Rhode Island

First. They were an all black regiment of 125

men, some free and some enslaved. There first

engagement was at the Battle of Newport in 1778.

At that battle, the Continental Army was forced

to retreat. The Rhode Island First put itself

between the retreating Americans and the

British. They were able to hold the line against

no less thant three British attacks. In these,

the British suffered heavy casualties. There

bravery saved lives and led to the transfer of a

Hessian officer. After the battle the officer

requested this transfer because he feared for

his life. He thought his own men would kill him

because of the heavy losses they took.

Rhode Island First Regiment - During the harsh winter at Valley Forge, a

new regiment was created, the Rhode Island

First. They were an all black regiment of 125

men, some free and some enslaved. There first

engagement was at the Battle of Newport in 1778.

At that battle, the Continental Army was forced

to retreat. The Rhode Island First put itself

between the retreating Americans and the

British. They were able to hold the line against

no less thant three British attacks. In these,

the British suffered heavy casualties. There

bravery saved lives and led to the transfer of a

Hessian officer. After the battle the officer

requested this transfer because he feared for

his life. He thought his own men would kill him

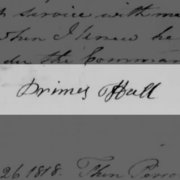

because of the heavy losses they took. Prince Whipple - Prince Whipple may have been a member of a

royal family in his native Africa. He was from a

rich family. When he was ten years old, his

family sent him to America to get an education.

But rather than arriving in America to attend

school. he was sold by the captain of the

ship into slavery in Baltimore. He was then

bought by the Founder William Whipple of New

Hampshire, who was also happened to be a ship's

captain.

Prince Whipple - Prince Whipple may have been a member of a

royal family in his native Africa. He was from a

rich family. When he was ten years old, his

family sent him to America to get an education.

But rather than arriving in America to attend

school. he was sold by the captain of the

ship into slavery in Baltimore. He was then

bought by the Founder William Whipple of New

Hampshire, who was also happened to be a ship's

captain.

James

Armistead Virginia slave, working with General Marquis de Lafayette as a spy

- By Wallbuilders

James

Armistead Virginia slave, working with General Marquis de Lafayette as a spy

- By Wallbuilders

October 19, 1781: The War for Independence Ends - The Siege of Yorktown was the final major military action in the War for Independence. This three-week long battle is significant in American history because it finally secured American independence after 6 years of active fighting.

A typically unknown aspect of the story of Yorktown is that a black man, James Armistead, played a major role in securing the victory. He was a Virginia slave who wanted to help his country. Four months before Yorktown he began working with General Marquis de Lafayette as a spy. He had successfully infiltrated the camp of Lord Cornwallis where he collected intelligence on British movements and reported them to Lafayette.

Lafayette recognized Armistead's importance to the American victory and later successfully petitioned for Armistead's freedom. (Virginia required an act of the state legislature to free a slave for meritorious service.) During the siege, Cornwallis was heavily outnumbered (about 17,000 American/French troops against his 8,000 British troops).

On October 16th, he attempted a last-ditch effort. Under the cover of darkness, the British attempted to flee but a storm arose, forcing them to remain. Running short of supplies and with reinforcements cut off, the British surrendered on October 19, 1781. (From: Black Patriots of the American Revolution)